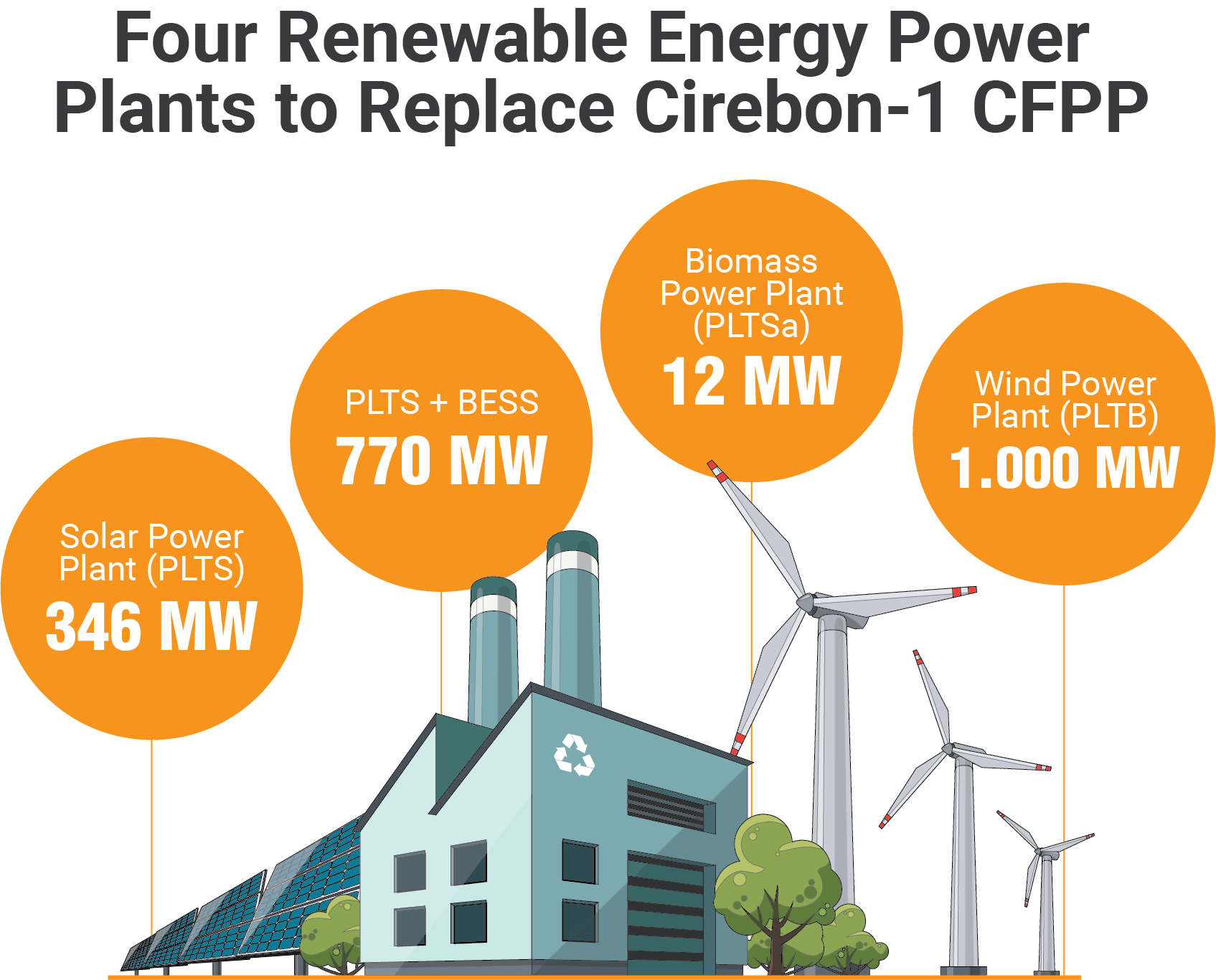

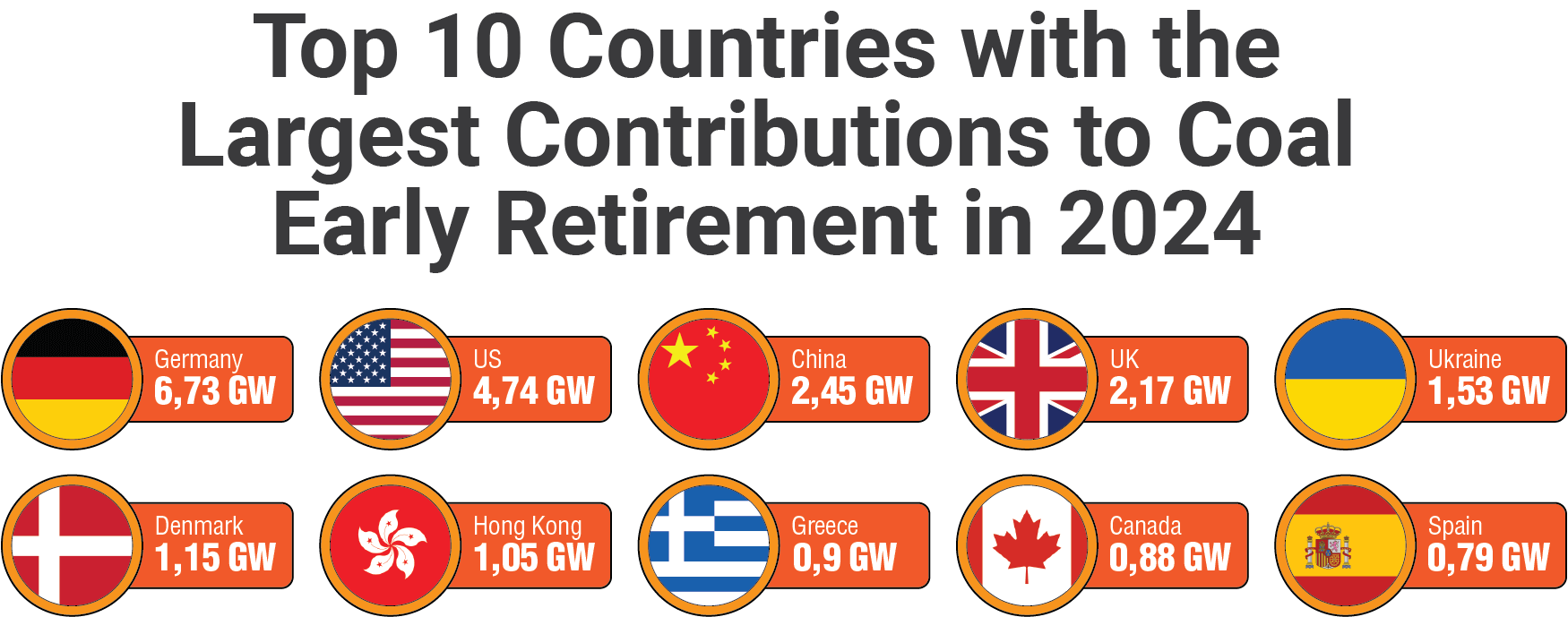

Financing is one of the most commonly cited challenges the Indonesian government faces in transitioning away from coal. The early retirement of the Cirebon CFPP, for instance, requires a loan from the Asia Development Bank according to Minister Lahadalia.

Such a project could cost the government US$4.6 billion (IDR 74.9 trillion at an IDR 16,300 per USD) if completed in 2030 according to the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR). If the timeline is extended to 2050, the cost could balloon to US$27.5 billion (IDR 448.2 trillion).

"Funding support for the early retirement of inefficient, costly, and highly polluting CFPs owned by PLN can come from the state budget (APBN). However, these funds, combined with state capital participation, must be used to accelerate the development of renewable energy and strengthen the electricity grid," said Fabby Tumiwa, Executive Director of IESR, in an official statement released in April.

Whilst costly, ISER strongly supports the retirement citing significant long-term benefits from the reduction in health costs and CFPP subsidies - which could reach up to US$96 billion by 2050.

On the contrary, continuing the development of CFPPs as business per usual carries a major potential for economic losses according to the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS). Construction of a new CFPP is estimated to cost Indonesia around RP 3.93 trillion, reflecting the negative impacts of coal power development on the overall economic output in affected regions.

“Such losses are largely caused by the environmental damage including challenges faced by fishermen to find livelihood, as well as the impact on the agricultural sector caused by coal mining activities supplying stock for the CFPP operation,” said Bhima Yudhistira, Director of CELIOS.

As a member of the JETP, Indonesia’s energy transition portfolio boasts a planned funding allocation of US$19.6 billion.

But a JETP Secretariat presentation in May highlighted that the majority of the partnership funds—about two thirds—comes from debt including commercial loans, concessional loans, as well as non-concessional loans. The remaining portion consists of equity investments, guarantees, and grants that could lead the funding parties to influence the transition process.

Domestic funding is undoubtedly the ideal solution to ensure Indonesia’s energy sovereignty—but where exactly can this financing be sourced from? This is where banking investments in the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) sector could serve as an important entry point to accelerate the development of renewable energy in Indonesia - particularly from the financing perspective.

Policy+’s ESG Outlook research report titled “Strengthening Indonesia's Banking Sector as Champions of Resilient and Greener Future” (2024), banks have begun channeling financing to renewable energy projects. Their portion, however, remains relatively small.

Bank Mandiri, Indonesia’s largest state-owned bank, has allocated Rp 8 trillion for renewable energy financing - which accounts for just 3% of its total green portfolio valued at Rp 264.1 trillion. Similarly, BCA, the country’s largest private bank, disbursed Rp 2.1 trillion—representing 1% of its Rp 202.6 trillion green portfolio—while UOB contributed Rp 242 billion, or 1.4% of its Rp 16.8 trillion green portfolio.

“Banks in Indonesia have indeed committed to achieving net-zero emissions targets and have demonstrated financing for renewable energy through the implementation of ESG. We see ESG investment as a gateway for banks to increase their financing portfolios in renewable energy sectors,” said Raafi Seiff, Founder and Director of Policy+, in a statement released last February.

However, Jalal, ESG expert and Chair of the Advisory Board at Social Investment Indonesia (SSI), stressed that true climate progress demands financial institutions to halt all funding for fossil fuel projects.

“If banks finance renewable energy but continue to fund fossil energy as well, it is essentially dishonest. Banks should gradually divest by stopping financing for new fossil energy projects,” he said.

According to a 2024 Climate Policy Initiative Indonesia report, the average annual investment in renewable energy power plants between 2019 and 2021 was US$2.2 billion—significantly below the required average of US$9.1 billion per year. This amount also pales in comparison to the average annual investment in fossil fuels during the same period which reached US$3.7 billion.

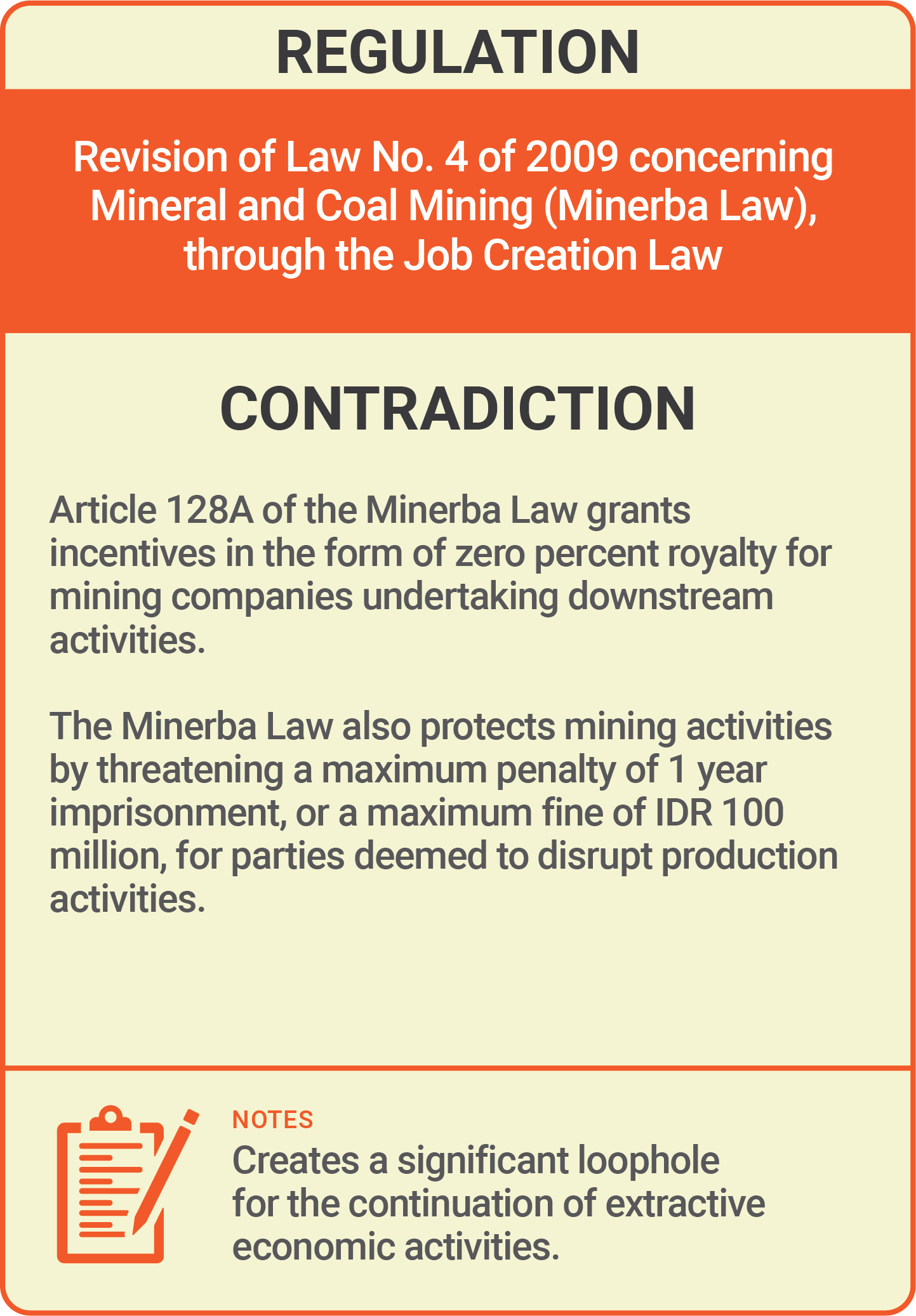

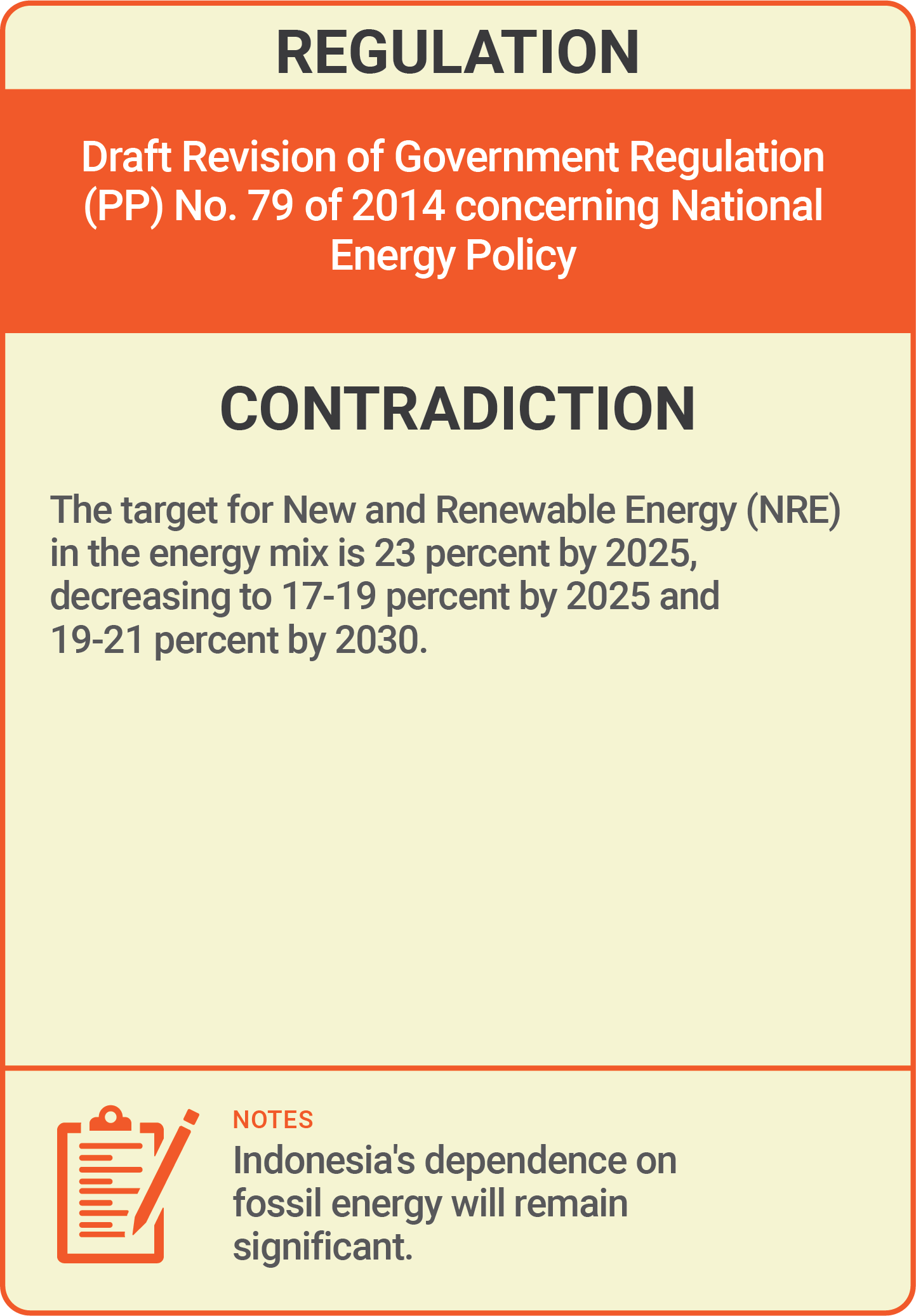

Indonesia has established the Sustainable Finance Taxonomy to guide financial institutions in responsibly channeling their funds. However, there is currently no legal enforcement to ensure its full implementation. Subsequently, it is important to note that coal-fired power plants (CFPPs) are classified as “yellow” within this taxonomy - meaning they are considered sectors that support the transition to a low-carbon economy and remain eligible for financing.

Tata Mustasya, Executive Director of SUSTAIN, highlighted several government options to accelerate the energy transition, including progressively increasing royalties and taxes on coal production.

“If the government has the political will to raise coal levies, Indonesia could actually finance its energy transition,” Tata said.

He also proposed implementing a carbon tax specifically targeting coal-fired power plants, with appropriate emission limits and pricing. Such a measure would reduce CFPP profits, thus discouraging coal operations and encouraging a shift toward renewable energy.

Indonesia could further generate funds to phase out coal-fired power plants by introducing a carbon tax. Although the carbon tax regulation was enacted under Law No. 7 of 2021 on Tax Harmonization, its implementation has been delayed until this year. Additionally, the current minimum carbon tax rate is only Rp 30 per kilogram of CO₂, far below the OECD’s recommended minimum price of US$60–75 per ton to effectively meet medium-term decarbonization targets.