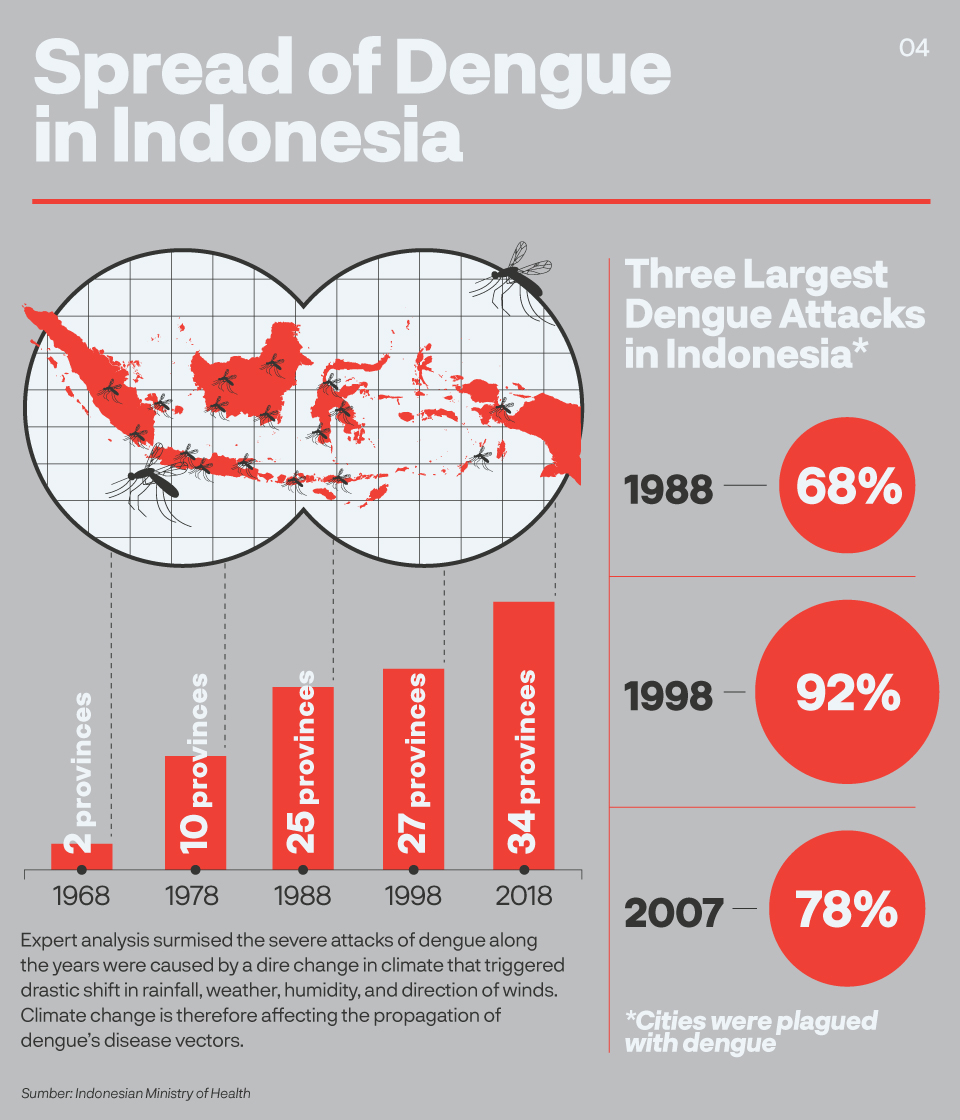

More than 50 people were seriously treated for a severe malady in 1968 Surabaya, of East Java. Rarely known to most people and even local health carers, their illness, characterised by fever, crushing bone ache and later haemorrhagic shock, eventually killed almost half of the patients.

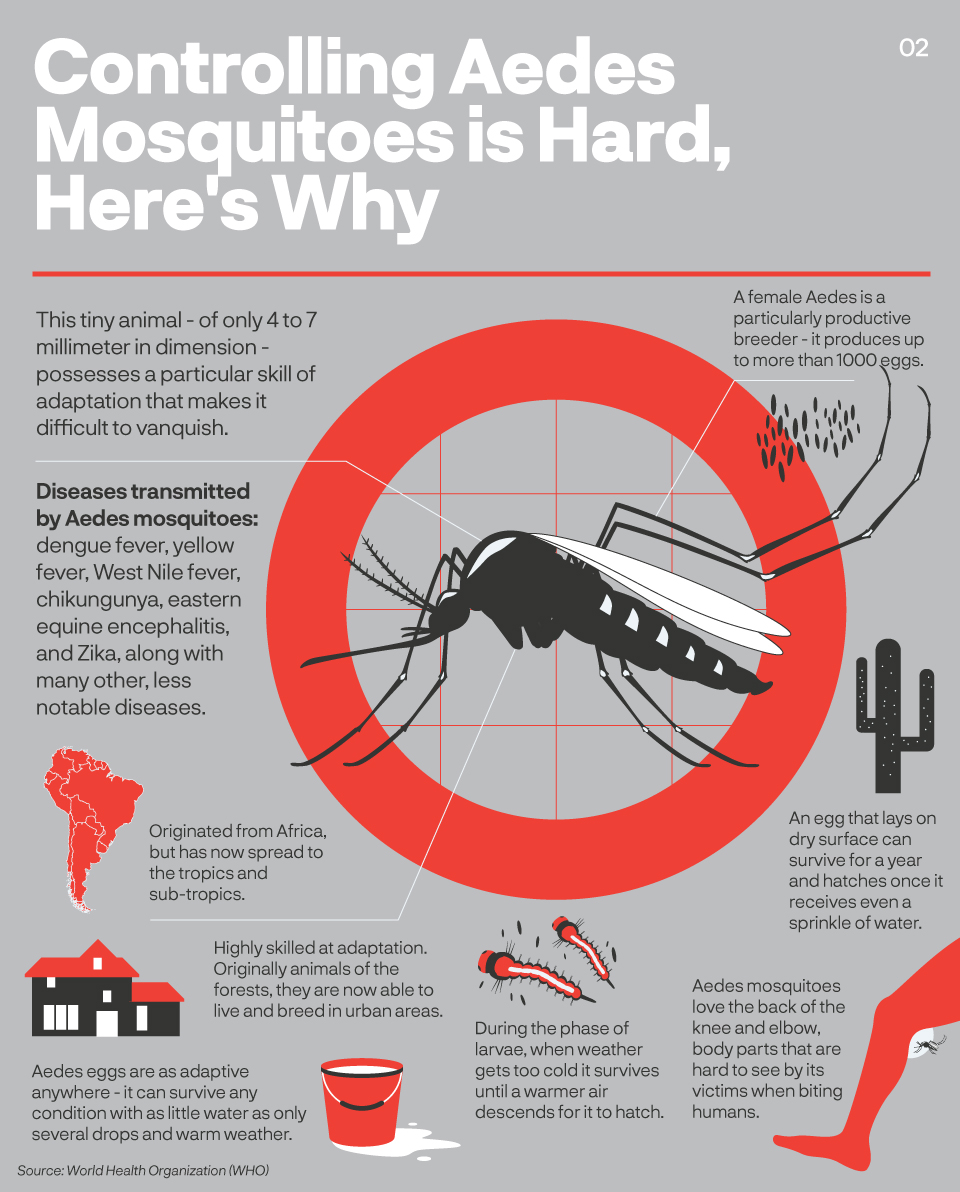

When science shed more light on the disease a decade later, it was subsequently known as dengue, an infection inflicted by aedes mosquito bites during daylight. From a densely populated kampung in Surabaya, it soon travelled around the country.

Dengue relishes on cities plagued with dense population, bad sanitation and poverty. After Surabaya, the second biggest city in Indonesia, it travelled to Indonesian capital Jakarta, and several major cities in Java, Sumatra, and Bali.

In 2015, yet the worst record for dengue outbreak in Indonesia, it killed 1229 people around the archipelago.

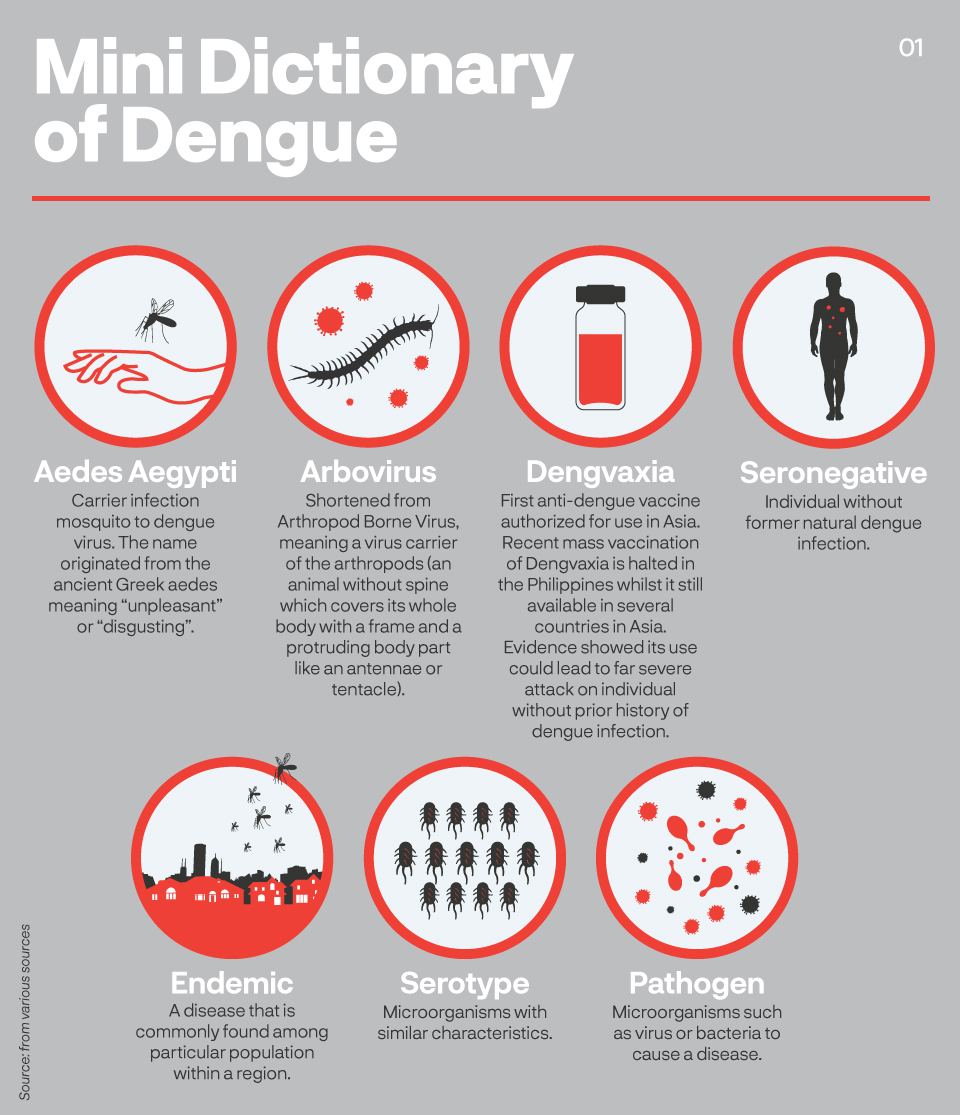

Science has since made several breakthroughs against dengue. The most advanced is the dengue vaccine, marketed by pharmaceutical giant Sanofi Pasteur. Dengvaxia, as the vaccine is named, was granted licence to be the first vaccine against dengue in Asia.

“Probably the most significant breakthrough… Although it has not been used widely because of its relatively low to moderate efficacy, this vaccine may still provide benefits for people living in dengue-endemic countries,” said Tedjo Sasmono, head of the Dengue Research at the Eijkman Institute in Jakarta.

Sasmono has been spending years on dengue vaccine research and currently leads a team over Indonesian dengue experts to investigate ways to prevent spread of the malady. What happened in the Philippines however, proves that the research into dengue vaccine may need longer years to complete.

Three months after its official launch in the Philippine in 2015, World Health Organization reported Dengvaxia may trigger more severe case in seronegative patients – those without history of prior dengue infection. An individual that has yet to sustain a natural dengue attack may suffer more malignant case of the infection if administrated a Dengvaxia.

A later report from Sanofi Pasteur confirmed this.

The public in the Philippines and Brazil, two countries of highly endemic dengue and first countries to authorize Dengvaxia, are furious: why was the risk not revealed before? The hope of preventing infection by vaccinating millions of school children in the Philippines turn to anger and disillusion.

On December 2017, Philippines Health Undersecretary Rolando Enrique Domingo said the government decision to halt Dengvaxia vaccination is not something to “change in one to two years.”

“Yes, it was disappointing,” said Veerle Vanlerberghe, an epidemiologist and disease control specialist for the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM) in Antwerp, Belgium. “We are hopeful, of course, but many scientists have been quite sceptical (about Dengvaxia). The vaccine alone is not the answer, it’s hardly the single bullet to eradicate dengue.”

So Vanlerberghe and scientists around the world keep on with research to find more efficient ways of battling dengue.

According to WHO dengue is now endemic in more than 100 countries in tropical and sub-tropical countries. Once seen as improbable, outbreak of dengue has also arrived in the Europe with cases detected in France and Croatia by 2010 and in Portugal by 2012. The meticulously clean Japan, after a period of absence for more than 70 years, has treated 18 patients from autochthonous dengue in 2014.

Within the global health vernacular, dengue is grouped under the “neglected tropical diseases” – recalcitrant communicable diseases that keep consuming lives in the tropics and subtropics.

According to WHO dengue “has taken the world by surprise” as its victims rose to 30 folds in the last 50 years. A coherent and coordinated efforts is thus crucial if countries are to save lives. Recent research are looking for best approach to either survey, prevent or control dengue.

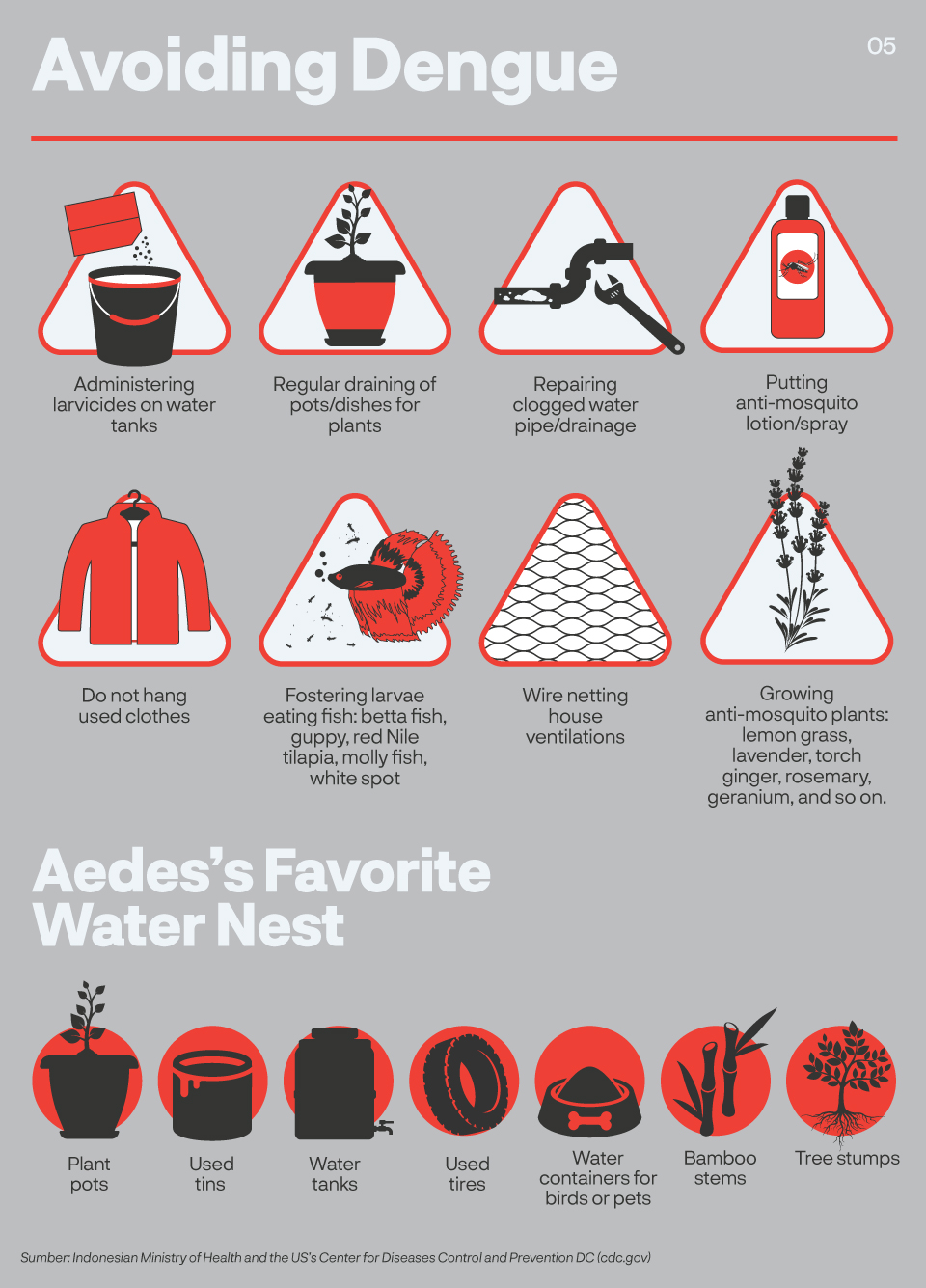

Veerle Vanlerberghe of the ITM in Antwerp, Belgium leads a research that focuses on a seemingly mundane question: if aedes mosquitoes attack during daylight, when most humans are at work, what type of prevention would protect people best?

“The target is to improve control measures. Most countries focuses prevention activities on houses before, because, understandably, it’s where the breeding sites are. But if we understand that children go to school, people go to work, in offices, markets, streets, buildings - should we consider different approach?” she asked.

Such model is common in Indonesia. The standard response to a new case of dengue is to pulverize victim’s residential area with anti-mosquito fogging, whilst evidence is unclear if infection took place at home. Also a frail strategy considering action is only taken when infection has already developed.

If aedes mosquitoes attack during daylight, when most humans are at work, what type of prevention would protect people best?

Establishing targeted areas on prevention programs would substantially change the game: from reactionary to precautionary. Instead of fogging houses - would it make more sense to do so in schools, offices or markets? Vanlerberghe hopes to find more conclusive answer from a larger study on human mobility and popular spots in 2019.

Studies on malaria elimination in Asia offer insight into why understanding mobility and population is key. Charlotte Gryseels of the ITM’s Department of Public Health runs several research projects and argues there is no one intervention that fits all.

“A Different kind of mobility introduces a different kind of intervention. Devising the right intervention would save live, funding and efforts,” Gryseels explained.

Spread of malaria decreased dramatically during the last decade in Asia but stopped short of complete eradication at several pockets in remote places including the Thailand-Myanmar border. A population of homogeneous Hmong tribe live between the sides of the two countries.

Whilst the use of insecticide laced bed nets as intervention measure in both countries, especially the Thai side, have been reported as successful, malaria continues to be endemic at the border. Gryseels studies found out the intervention program seemed oblivious to several issues.

“There are different kinds of mobility that influences the way they contract malaria but also the way they use malaria prevention measures in a very different way. For example this slash and burn farmers. They stay in the field for one season and even have a house on this field. But it was really far away and makes it uncomfortable for them to bring bed nets.”

Other population onsite are the plantation workers, even from lower social and economy rank compared to the farmers, where few are registered to receive bed nets. Existing intervention with bed nets is therefore may not be the most efficient. Which begs the question: are there better options?

“In the end it’s about mapping out this mobility and convincing authorities to intervene with the right population,” Gryseels concludes.

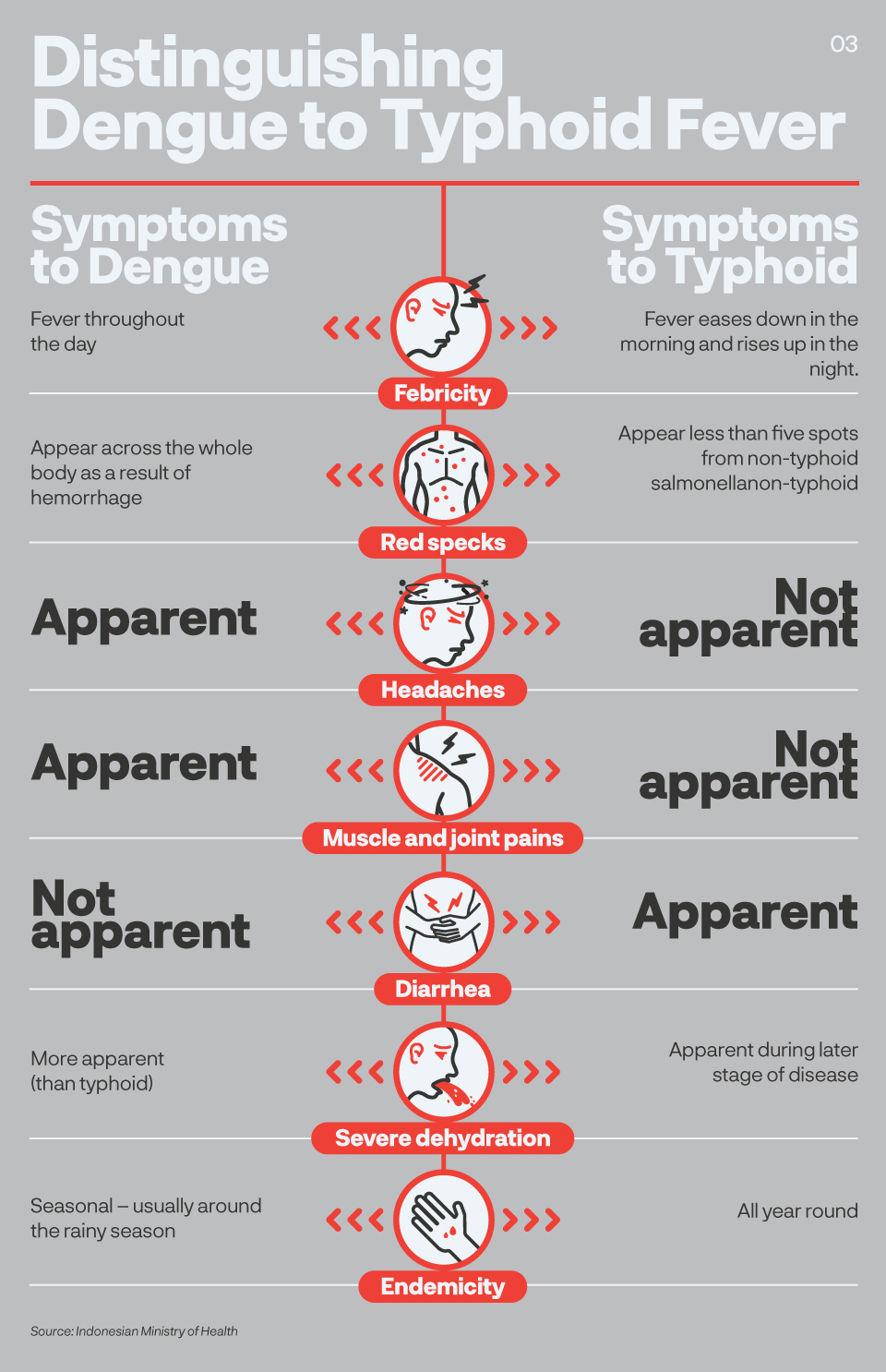

Several thousand miles away in Aruba, a tiny island off the coast of Venezuela, Ralph Huits faced a different situation. He served as a medical doctor in the Caribbean island in 2010-2012 when dengue wrecked an epidemic. Unlike malaria where infection can be determined quickly using Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT), dengue takes longer as symptoms usually only start 3 to 7 days after a patient is bitten by an infected aedes mosquito.

This is problematic.

“Doctors are very poor at predicting dengue. Hard to tell who is going to be okay and who is going to need further treatment”, said Huits who is currently leading the Fever Study at the ITM.

It means even when people come early with complaints of fever, joint aches and other common dengue symptoms, physicians cannot be certain to administer a treatment. Consequently, when diagnosis of dengue is established, infection could have gone more severe or even caused a fatality. Based on his experience and several other studies in Brazil, Huits suggested a test on certain blood protein for faster prediction.

“The ferritin - that is the protein that transports iron to the blood, level is normally between 50-200 micrograms per litre (of blood). In any infection they will go up a bit…. What I found in dengue patients that were admitted into the ICU, they were not hundreds, or thousands, they were 70 or 80,000 micrograms per litre. So really very, very, very high. And in internal medicine, there is only a few of infection with this sign,” explained Huits.

In several papers published by the Neglected Diseases Journal, including Huit’s own, the research suggest that a test on ferritin level may give a strong indication of dengue, hence accelerates medication and saves lives.

The WHO stated medical care on severe dengue from physicians and trained nurse decreases mortality rates from more than 20% to less than 1%, a later diagnosis is therefore damages the opportunity. WHO has since urged the health services to admit patients with warning signs regardless of diagnosis.

Current science established four types of dengue identified as DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3 and DEN-4. Recovery from one particular type of infection provides lifelong immunity against said serotype, but not to others. Risk of developing more severe dengue could transpire if an individual is inoculated with Dengvaxia whilst never had prior natural dengue infection.

After the commotion with Dengvaxia, ITM’s Virologist Kevin Arien focuses his research on designing diagnostic kits to establish serotype history: whether one has been infected before and what type of infection he/she has. Knowing one’s history against dengue would tremendously help with assigning vaccination to proper individuals. The current set of diagnostics for dengue, Arien said, is inadequate. His challenge comes, again, from the myriad of viruses that are hard to detect after years of infection.

“We’re looking at antibodies that result from an infection several years ago – maybe 5-10 years ago. That’s where the difficulties with the current assays… They are not good to predict the serostatus. It’s clear that right now companies, after what happened with Dengvaxia, diagnostics companies and even pharma companies like Sanofi are forced to rethink diagnostic tests,” said Arien.

Detection of outbreak and its containment for infectious diseases is highly dependent of this test.

“Do you have a proper test to find or pick-up the virus or any response that’s directed against the virus? So it all basically starts with a good proper diagnostics. However, as is often, it’s being overlooked. These companies rushed in with vaccines, rushed in with therapies, and forgot about the test that needed to measure whether their vaccines or therapies are doing something,” Arien snubbed.

For the current project, he is using similar base from his previous project of diagnostics set to determine ebola infection. Developed into a compact tool the size of a little bigger than usual coffee mug box, it was designed to be used with minimal help from elaborate lab equipment to mimic real ebola fields in Africa. But even with the experience, he estimated the quest for a reliable dengue serotype status diagnostics kit will take 3-4 more years to completion.

The chronicle of Dengvaxia has also once again proved that there is no easy way to beat dengue. Big funding and last three decades of research are yet to provide the desired results.

Hopefully, there are more to come. Medical student Aran Sandrasegaran noted that until 2016 there were at least seven global efforts to develop anti-dengue vaccine. Those leading the process include drug maker Glaxo-Smith-Kline which partners with Walter Reid Army Institute of Research, and Mahidol Institute in Thailand which collaborates with, also, Sanofi Pasteur.

Similar problem emerges. Identifying dengue from other emerging febrile diseases caused by arboviruses with identical symptoms, such as zika, yellow fever, encephalities or chikungunya, and creating a fully functional vaccine is one of science’s current biggest challenge.

“From the pathogen’s side, the presence of four different dengue virus serotypes circulating and infecting people is one of the factors contributing to the complexity of the research in dengue,” said Tedjo Susmono of the Eijkman Institute, himself researching dengue for the last 20 years.

“The diversity of viruses also accounted for the transmission competency and epidemic potential, as well as in some degree influencing the severity of the disease.”

According to Sasmono’s research, the four serotypes have been widely circulating in most of urban Indonesia, and more than half of children had already been exposed to more than one dengue serotype thus demonstrating intense transmission often associated with more severe clinical episodes. With knowledge like this, he hopes Indonesia could contribute to the development of dengue diagnostics, drugs and vaccines that is more sensitive and specific to be used in Indonesia.

-

Writer: Dewi Safitri

-

Editor: Vetriciawizach Simbolon

-

Graphics: Fajrian, Asfahan Yahsyi

-

Graphic Assets: iStock

-

Page Layout: Fajrian, Muhammad Ali